By Elton Alisson | Agência FAPESP – Autopsies performed in the past four months on approximately 70 COVID-19 patients who died in the city of São Paulo, Brazil, showed that some died mainly due to cardiovascular alterations caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 and not by respiratory failure. The patients were diagnosed and treated at Hospital das Clínicas (HC), which is the general hospital run by the University of São Paulo’s Medical School (FM-USP) and the largest hospital complex in Latin America.

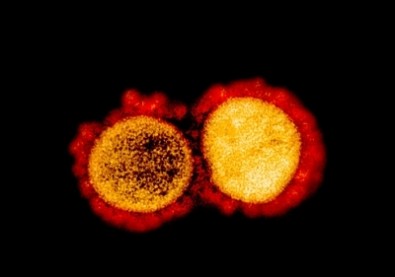

Scientists are now investigating the viral action mechanism that causes alterations in the micro- and macrocirculation as well as epithelial lesions in practically all vital organs.

“We know the virus spreads to organs like the brain and kidneys, as well as salivary glands and gonads, for example. It also reaches the central nervous system via the olfactory nerve. Now we want to know how it causes clotting in the micro- and macrocirculation far more severely than influenza viruses, for example,” said Paulo Saldiva, one of the project leads, in an online discussion about the COVID-19 epidemic in Brazil held on July 13 during the Virtual Mini Annual Meeting of the Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science (SBPC).

The event was an abridged online version of SBPC’s 72nd Annual Meeting, scheduled to take place on July 12-18 at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN) in Natal (Northeast Brazil), but the full event was cancelled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to Saldiva, the autopsied patients diagnosed with COVID-19 who died as a result of cardiovascular alterations caused by the novel coronavirus included children aged 8-11 as well as adults. “Their lungs were reasonably well preserved, but they developed very intense heart failure, which led to death,” he said.

In some cases, the researchers identified the presence of the virus in the myocardium (the muscular layer of the heart). In others, the researchers observed clotting in the pulmonary and cardiac microcirculation.

“We want to understand the causes of this situation to be able to help and intervene sooner in the treatment of these patients. This is one of the goals of the project,” Saldiva said (read more at agencia.fapesp.br/32955/).

The autopsy procedure is performed using minimally invasive techniques guided by imaging methods to scan all internal organs and collect tissue samples; this process was developed as part of a project supported by FAPESP.

Segmented mortality

The researchers obtained the medical histories of patients who died in the hospital from COVID-19 at the same time as when they asked the families for permission to perform an autopsy. According to Saldiva, the families’ responses indicated that almost all the patients and their next of kin were well aware of the risks of catching the disease but were unable to self-isolate.

“The families said they couldn’t self-isolate because they lived in crowded dwellings,” he explained.

Data on the origin of these patients also reinforced the researchers’ conviction that the risk of dying from COVID-19 in Brazil is far greater in socioeconomically disadvantaged regions.

“The risk of falling ill from COVID-19 in Brazil isn’t as characteristically segmented by socioeconomic status, but mortality is, and two factors responsible are housing, and above all, commuting by mass transit,” Saldiva said.

“Urbanization and migration are the main drivers of the mutations in respiratory viruses that have been the foremost causes of pandemics since the start of the twentieth century”, he added.

The twentieth century observed two respiratory virus pandemics – the Spanish flu in 1918-20 and the Asian flu in 1957-58 – while the present century has so far seen two pandemics per decade. “There was SARS in 2002-04 and H1N1 in 2009,” Saldiva said. “MERS followed in 2012 and the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic that started in late 2019 or early 2020.”

“Having vaccines to combat these diseases is desirable but not sufficient,” he added. “We need effective systems to test for and identify the viruses in all countries.”

In addition, he said, more international cooperation is needed, as well as funding for more studies in the field of health by researchers not just in the life sciences but also in the humanities.

“You can’t control epidemics without knowledge of anthropology, history and urbanism,” he said.

This text was originally published by FAPESP Agency according to Creative Commons license CC-BY-NC-ND. Read the original here.